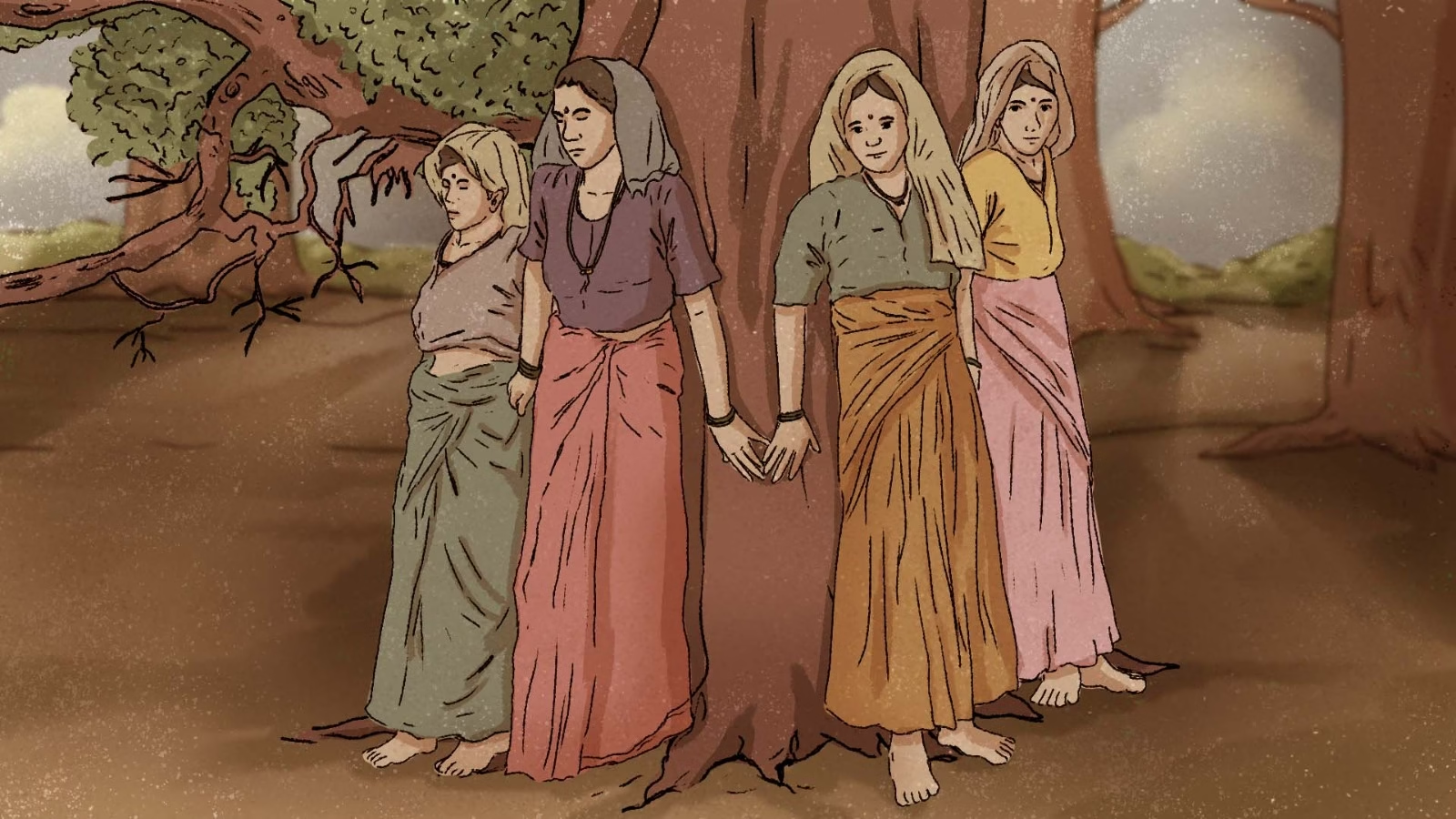

On a spring morning in 1974, twenty-one women of Reni village in Uttarakhand walked quietly into the forest. They weren’t carrying placards or microphones. They had no legal permits, no contracts, no security. What they had was their bodies and a simple determination not to let the axes fall. Led by Gaura Devi, the women wrapped their arms around the oak trees that gave them fodder, fuel, and fibres. When the loggers arrived with orders from the state, they met not wood but the unyielding presence of women who declared the forest to be their maika: their mother’s home.

That image of women embracing trees became one of the most enduring photographs of resistance in India. But behind that moment was not just courage. There was storytelling, symbolism, memory, and an unbroken thread of communication that reached from a mountain hamlet to the Prime Minister’s office in Delhi, and later, to movements across the world. So let’s dive in and see what Chipko, five decades on, can teach us about how stories can be told, carried, and sustained.

The Songs That Stitched Villages Together

Chipko did not only unfold in forests; it travelled through voices. Ghanshyam Raturi, known as Sailani, carried his harmonium and sang verses that wove survival with hope: “For forests are our life and soul, they are the sources of rivers all.” Villagers would gather, repeat, and carry these songs to neighbouring hamlets. One of his collections, Ganga Ka Mait Biti, sold for just ₹15 but captured the pulse of an entire movement. Songs turned protest into memory; they gave people a way to participate even when they could not stand in front of the trees themselves.

Songs gave people a way to participate even when they could not stand in front of the trees themselves.

For campaigns today, the lesson is clear: music and rhythm embed messages where reports cannot. A chorus repeated in the local idiom can stitch a cause into people’s daily lives, making the story something they sing, not just something they hear.

A Slogan That Needed No Explaining

If Chipko had only been about hugging trees, perhaps its story would have stayed in the hills. But slogans gave it wings. The chant, “What do the forests bear? Soil, water, and pure air”, captured everything the movement stood for in ten words. Bahuguna’s equally resonant line, “Ecology is permanent economy,” reframed conservation as livelihood, not luxury.

Chipko teaches us that the best slogans are not manufactured but harvested from community urgency.

Lasting campaigns often rise and fall on a phrase that is chantable, memorable, and, more significantly, nimble enough to bypass geographies. Chipko teaches us that the best slogans are not manufactured but harvested from community urgency.

When a Photograph Speaks for a People

The embrace at Reni was not the first confrontation, but it became the most recognisable because it was seen. A local photographer captured women locking arms around tree trunks as men with axes looked on. Later, press images showed villagers tying sacred threads to trees, or bandaging the wounded bark of pines tapped for resin. These visuals, once printed in Delhi newspapers, condensed the struggle into a “photo sentence” that needed no translation.

When a story is told visually in a way that anyone can decode at a glance, it becomes unforgettable.

Campaigners today know the flood of images that compete for attention. Chipko reminds us that one strong frame can cut through the noise. When a story is told visually in a way that anyone can decode at a glance, it becomes unforgettable.

Theatricality as Strategy

Sunderlal Bahuguna’s 5,000-kilometre padayatra across the Himalayas between 1981 and 1983 was not only a march. It was theatre on the move. At every halt, villagers welcomed him with songs, schoolchildren repeated slogans, and gatherings turned into performances. Earlier, Dasholi Gram Swarajya Mandal had used padyatras, petitions, and encirclements as a choreography of protest: villagers would form circles around trees, sing, hold ground, and call the press.

These carefully staged acts made resistance visible without a single press release. For NGOs, this is a reminder that activism can be choreographed for impact. When the act itself becomes theatre, the story writes itself into public consciousness.

The Hook That Carried It Beyond the Hills

Chipko’s genius was not just in doing but in being seen. By the late 1970s, Delhi and international newspapers had adopted the image of women tree-huggers as the shorthand for the entire movement. Scholars like Arvind Singhal note that this was not accidental; activists ensured that reporters had images, that chants were repeatable, and that leaders like Bahuguna bridged local protest to national discourse. By 1980, Indira Gandhi’s government announced a 15-year ban on green felling above 1,000 metres, citing Chipko. Later, the Supreme Court extended restrictions in 1996.

A story that is easy to retell is one that survives long enough to make policy.

For communicators today, the point is not about courting headlines but about shaping a hook that journalists, donors, and allies can carry forward. A story that is easy to retell is one that survives long enough to make policy.

Carrying Chipko Forward

Chipko was never just about saving trees. It was about saving stories; through song, through slogans, through images, through marches, through the way one act of resistance could echo across continents. Its echoes can be heard in Sweden’s tree-hugging protests of 1987, in Japanese citizens circling Mount Takao in 2008, and in the countless campaigns that now place frontline women at the centre of ecological narratives.

For NGOs today, Chipko is less a manual than a mirror. It shows us that movements rise not only on the strength of their demands but on the stories that carry them. A folk song that lingers, a chant that rallies, a photograph that moves, a theatrical act that captures attention, a media hook that translates local struggle into national policy; these are not side notes to activism but activism itself.

Half a century later, the women of Reni still stand in that clearing, their arms around the trees, reminding us that the embrace of Chipko was also an embrace of story, one that still teaches us how to hold on.

Receive Stories and Tools That Make an Impact

Interested in more examples like these, along with suggestions for your nonprofit to develop campaigns that touch hearts, build trust, and improve donor engagement? Sign up for our newsletter. Each issue is full of great ideas for compelling storytelling, ethical communications, and using your mission to create real, measurable change.