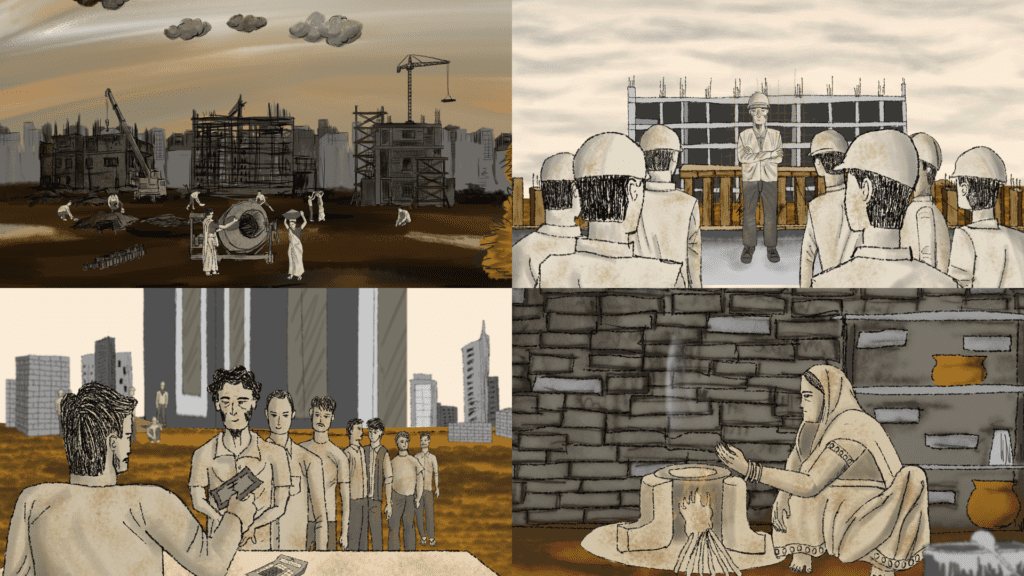

Ramesh is on a construction site, doing what he always does: showing up early, keeping his head down, and hoping he gets paid on time. But his wages are withheld. A debt starts to grow. Threats begin to creep in, not just for him, but for his family too. It is the kind of situation that can turn a job into a trap, and it often stays invisible because it happens in plain sight.

That is the human thread running through the animated short we created with the Global Fund for Ending Modern Slavery (GFEMS). GFEMS exists to end modern slavery by supporting grassroots organisations and survivor-led initiatives. As part of their work, they commissioned a study on India’s construction sector that surfaced something crucial: micro-contractors can play a real role in preventing exploitation and safeguarding vulnerable workers, especially when formal business practices and ethical norms are taken seriously. They wanted a film that could carry those findings beyond a report and into conversations that lead to change.

So we were brought in to translate the study into a short animated film that could work as an advocacy tool. The aim was clear: make the issue understandable, make the recommendations memorable, and do it without flattening the lived reality of workers into dry information.

Why we leaned on a character-led story

We could have made a purely informational explainer. But modern slavery, debt bondage, withheld wages, intimidation, these are not abstract concepts. They land on a person’s life, one decision at a time. That is why the film centres Ramesh. His story creates an emotional entry point, and it also gives the research somewhere to live.

Ramesh’s story creates an emotional entry point, and it also gives the research somewhere to live.

By following him through exploitation and then towards change, the film can show what GFEMS is actually advocating for: practical steps that micro-contractors can take to reduce harm, improve accountability, and protect workers. The research stays present, but it rides on a narrative people can follow.

Finding the right animation style

Early on, we spent time in discussion and brainstorming with the GFEMS group. A big part of that phase was exploring different visual directions. We tested various approaches to drawing and animation before landing on a multi-layered 2D method that felt distinctive. We wanted the film to hold attention, but not feel shiny or overproduced. It needed to feel purposeful and grounded.

This is also where colour came in. We chose the colour palette to match the study’s focus, so the visuals stayed with the story instead of pulling attention away. The colour decisions were about mood, clarity, and emphasis, not decoration.

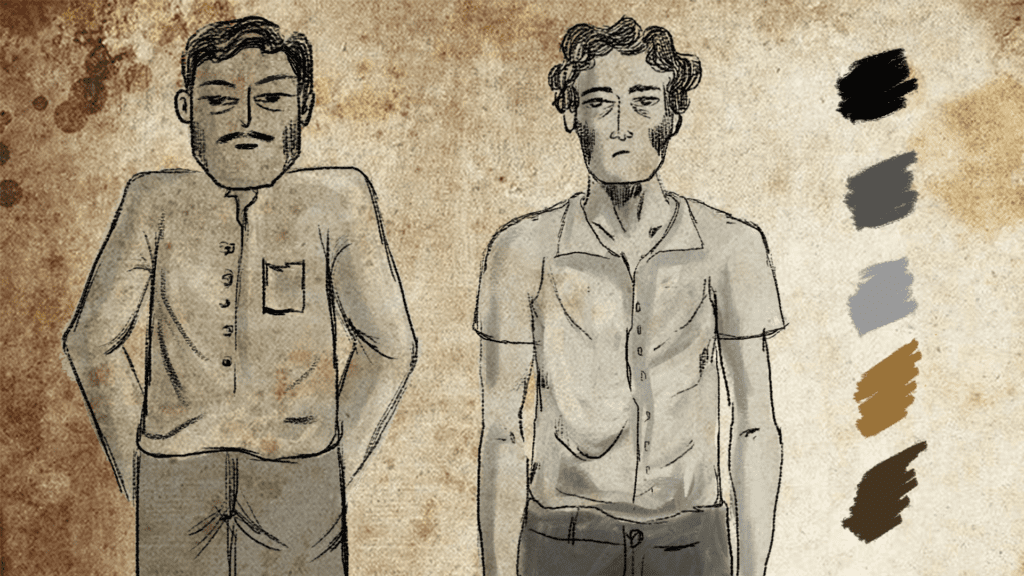

Character design that carries meaning

In projects like this, character design is not a cosmetic step. It is where dignity and believability are either protected or lost. We developed the characters carefully, including Ramesh and Guddu Mama, working through iterations until their faces, posture, and styling felt right for the world they inhabit.

Suggest enough for the message to land, but never turn suffering into spectacle.

We paid attention to how the characters sit in a frame, how they react, and how much we show versus imply. Ramesh’s experience includes fear and pressure, but we did not want to dramatise it. The goal was to feel real, not performative. The same principle guided how we visualised exploitation. Suggest enough for the message to land, but never turn suffering into spectacle.

Getting the voice right

One of the most important decisions we made was around voice. Accent can instantly make a character feel authentic or artificial. Since the film needed to feel rooted, we brought in a regional theatre artist to give Ramesh an accent grounded in Bihar. That single choice added a layer of realism that visuals alone cannot deliver.

Voice also affects trust. If the voice sounds generic or overly polished, viewers switch off, especially when the subject is worker rights and justice. We wanted people to feel like they are hearing someone who could exist beyond the screen.

Sound and pacing with intent

Once animation and voice begin to come together, sound design becomes the glue. It shapes how the film feels in your body. We approached sound and music with care so that it supported the story rather than pushing emotion too hard.

Editing mattered here too. The film has to move, but it cannot rush. We wanted enough breathing room for the recommendations to register, and enough steadiness for the story to feel credible. Every cut was about keeping the viewer oriented: where we are, what is happening, and why it matters.

Turning research into an advocacy tool

By the end, the film does two jobs at once. It carries Ramesh’s story with empathy, and it amplifies the recommendations from GFEMS’s construction sector study in a way that is accessible to a wider audience. That balance was always the point. Advocacy content only works when people understand the issue, feel its weight, and can see what action looks like.

If your organisation has strong research, community insight, or lived experience that deserves more than a PDF, animation can help you carry it further. And if you want a film where every creative choice is tied back to dignity, accuracy, and impact, we would love to collaborate.

Client: Global Fund for Ending Modern Slavery

Discipline: Films and Photography

Creative Director: Simit Bhagat

Animator and Editor: Rohan Krishnan

Illustrator: Sonali Gupta and Kumar Shradhesh Nayak

Script: Beth Garcia and Simit Bhagat

Hindi Translator: Bhumika Sharma and Vivek Singh

Creative Advisor: Joel Machado

Sound Design and Music: Raju Das

Voice Artist: Mohd Ikram