In this interview for our Leadership Series, Osama Manzar shares the journey that led him to found the Digital Empowerment Foundation (DEF) and reshape the digital landscape for rural India. Reflecting on his childhood in Champaran, Bihar, and the challenges he faced in both personal and professional life, Osama discusses the values that have shaped his leadership and his commitment to empowering underserved communities. He explores the importance of following one’s passion, the role of resilience and self-awareness in achieving success, and how his approach to leadership has evolved, touching on storytelling, compliance, and balancing personal visibility with the organisation’s strength.

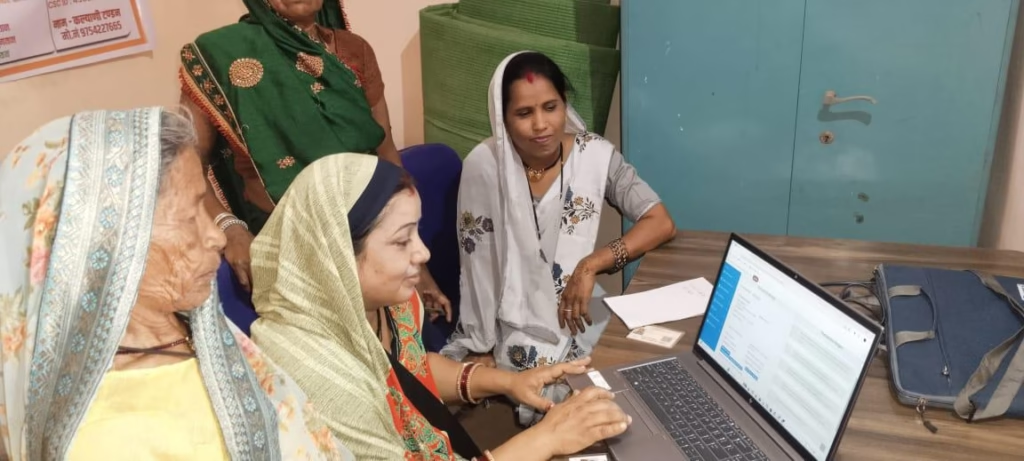

Osama Manzar is the founder of the Digital Empowerment Foundation (DEF), an initiative that has transformed India’s rural communities by providing digital skills and access to government services. With over 10,000 digital foot soldiers and 1,000 community hubs across India, DEF’s work has touched the lives of over 35 million people, including women, youth, and people with disabilities.

If you’re interested in the intersection of leadership, personal growth, and social impact, this interview offers valuable lessons on staying true to your values while scaling change.

Transcript of the Interview:

Simit: Welcome, Osama. It’s such a pleasure to have you here. You’ve had such a fascinating journey—from engineering to the Air Force, to journalism, and now decades in the development sector. To start us off, how important has it been for you to always follow what you truly love doing?

Osama: So first, just to clarify—I’m not an engineer. I kept trying, but it never quite worked out. What pushed me into all these different spaces wasn’t ambition, really. It was discomfort. I wasn’t okay with settling. A lot of people accept the situations they’re given—I couldn’t.

Looking back now, it probably began in childhood. I grew up in Ranchi, but I also spent my summers in Champaran, Bihar. And those two months of village freedom were deeply formative. I could roam, explore, and do what I wanted. It left a deep imprint. But then I’d return to Ranchi—timetables, school bells, my disciplinarian father who believed in punishment to set you straight.

So I grew up torn between liberty and control. And my spirit naturally leaned toward freedom. I didn’t realise it then, but I was someone who needed space to experiment, to fail, to find my own rhythm. While my cousins pursued careers in engineering and medicine, I struggled. I kept trying. I studied physics not because I loved it, but because it was challenging, and I hadn’t been accepted into anything else.

Then came the Air Force. But I quickly realised that as an airman, I was just another cog—there was no dignity, no autonomy. Leaving the defence forces isn’t easy—it’s like being stuck behind a barbed-wire border. But I made it out. And honestly, that escape was a turning point. It was resilience. The resilience of someone who had never been validated, who had only heard, “This isn’t good enough.”

From 14 to 27, nothing came easily. I didn’t know what a confident decision felt like. Everything I touched went wrong. Then I got my first real break at Down to Earth. But within two months, I was let go. My editor didn’t think I could write well. He made me rewrite the same report a hundred times. Eventually, he told Sunita Narain (Director General of CSE and editor of Down To Earth) I wasn’t fit for the role—and she agreed. She said, “If your boss doesn’t want you, I can’t force it.” And that was that. I had to leave.

But life has its way of circling back. Fifteen years later, Sunita Narain herself invited me to be on the Down to Earth board. That moment wasn’t about revenge—it was about coming full circle with grace.

I’ve never blamed those who rejected me. I didn’t come from an English-speaking background. I had to fight for every sentence to be taken seriously. But then ComputerWorld gave me a chance. My editor there told me something simple: “You’re not here to write fancy sentences. You’re a correspondent. Just bring me real stories.” That changed everything.

Eventually, I even wrote a column for LiveMint for ten years—not because I became a great writer, but because I had something real to say. Leadership, to me, is the same. It’s not about shouting or demanding, but about making people do great work without even realising they’re being led. It’s about staying self-aware, staying curious, and building something that lasts—quietly, steadily, without applause.

Leadership is not about shouting or demanding. It’s about making people do great work without even realising they’re being led.

Simit: Yeah, there are so many threads I want to pull at—it’s hard to pick just one.

You mentioned growing up between two very different spaces—Ranchi, which was in Bihar at the time, and then the village in Champaran where you felt freer.

When you look back now, as a leader, do you feel like that mix—the discipline of a strict father and the liberty of village life—shaped how you respond to people today?

Do you sometimes catch yourself wondering, “Am I being too critical? Am I expecting too much?”

Did that early experience of trying to please someone who was never quite satisfied influence how you lead or relate to others now?

Osama: Yes, absolutely. And I think one of the biggest testaments to that is the way my wife and I have built our life together. We’ve been married for almost 30 years now and have been together for 34. Our eldest child is 27, the younger one is 23. And across these years, the one thing we’ve consistently done is take what we’ve learned from the world around us, and implement it in our lives almost completely upside down.

But we never did this to prove someone else wrong. That was never the point. Others were also right in their own way, perhaps. But our “right” looked different. It didn’t come with patriarchy. It wasn’t built on gender bias or caste hierarchies. Our rights didn’t involve subjugation or control. It didn’t place value on someone’s ability to speak a particular language or to meet certain age expectations. It didn’t rest on certificates.

You were right. I was right. You did five namaz, and I didn’t—but I still spoke the truth. You were law-abiding, and so was I. So then, what made one of us more “successful” than the other?

You know, there’s that moment in 3 Idiots, when Aamir Khan says, “Kabil bano, safalta jhak maar ke peeche aayegi.” Be capable. Success will follow. That line really stayed with me.

Be capable. Success will follow. That line really stayed with me.

At one point, when my father and others felt I had finally “succeeded,” I had to sit him down and ask: Why do you think I’m successful now? Am I a different person today? Because, even before this, I had never stolen. I never broke the law. I never disrespected anyone. So why am I suddenly worth celebrating?

The problem is that people treat success as a moving target. First, it’s a job. Then it’s a house. Then it’s becoming CEO. But that’s just scaling. That’s not success. The milestones keep shifting.

I didn’t tick any of the conventional boxes—graduate, postgraduate, whatever. But I still ended up going to Manchester. I still received a Chevening scholarship. And I didn’t have to sit for an exam to get it. They simply asked me to join. I wrote a book—not because I had a PhD—but because I had something to say. Later, people from academia told me, “This is so well-researched, you should be teaching with us.”

Was it perfectly written? No. I didn’t grow up writing polished English. I wrote it however I could. And then I got it edited.

My children? They’ve never taken a formal exam in school. They were educated outside that system. Even today, my son—who is now doing his PhD—finds it hard to write structured exams. However, he has already written two books. And that didn’t come from boxed learning. That came from life.

We often believe that to solve business problems, you need an MBA. I say it’s the opposite. You can solve many problems without one—if you’re paying attention to what life is teaching you.

We often believe that to solve business problems, you need an MBA. I say it’s the opposite.

It’s not just about degrees. You don’t have to be Muslim to read namaz. You don’t have to be Hindu to visit a temple. What you need is the right tool—and the wisdom to know when to use it.

In our case, we didn’t follow the classic nonprofit structure. We didn’t rely on rigid processes. Yet, we have a team of 300–400 people, 2,000 centres, a global network, and we’ve impacted 35 million lives. We’ve grown organically, not by force.

Interestingly, someone even did a PhD on our approach. They called it the “bricolage method”—where you create from what’s available, where you innovate as you go.

So yes, it’s a long answer. But to me, the point is simple: if you can develop enough self-awareness, intelligence, common sense, and correlation, then you can use the tools life gives you. And if you do that, you won’t just succeed—you’ll make your life useful. And I’d rather be useful than be called successful.

If you can develop enough self-awareness, intelligence, common sense, and correlation, then you can use the tools life gives you.

Simit: Yeah, I mean, growing up in a strict environment, for example, my father was very strict, and I couldn’t do much. You were in school, living in the same house, and it felt like you couldn’t stop thinking or writing the way you wanted to.

But as you grow older, and especially when you go to college, things start to change. You begin to rebel. At least, that’s what happened to me. I ended up resisting even more, simply because I was being forced into doing things I didn’t want to.

So, did you experience a similar kind of rebellion in your case as well?

Osama: Yes, I would say that. It did happen. I remember giving a talk at Jagriti Yatra once, and they asked, “What’s your journey of entrepreneurship?” I didn’t just consider entrepreneurship in the context of organisations. I said that my life, and the lives of many others, have been a journey of entrepreneurship.

One of the biggest definitions of entrepreneurship, I think, is taking risks. In other words, being a rebel. Sometimes, taking the risk of being a rebel means stepping outside the norm. If you don’t take those risks, you just follow what everyone else is doing. But, unless you’re a rebel, unless you take those risks, you’ll never truly see the other side of the world.

One of the biggest definitions of entrepreneurship, I think, is taking risks. In other words, being a rebel.

My first example of entrepreneurship goes back to when I was in ninth grade. I had this infatuation with a girl, and I was in a strict environment. Yet, at 2 AM, I would sneak out, open the door, and go meet her. Now, when I think about it, I wonder how I had the courage to do that. Eventually, I got caught, and my father shaved my head and sent me back to the village for a few months. That was my first experience of taking a risk to do what I wanted.

The second time was when I joined the Air Force. I had the courage to leave and return when I knew it wasn’t right for me. The third time was after graduation, when I chose a career in journalism. I didn’t follow the conventional path or what the world expected of me. I followed my heart, looked at all the options and decided on journalism because it appealed to me, I was passionate about reading the newspaper every day, and it felt like the right fit for me.

The fourth time was when I spent four years jobless and penniless, living in the slums around JNU. I never gave up, though. I didn’t give up on getting a job, and I didn’t give up on pursuing my dreams.

The fifth time was when I got involved with a girl at JNU who wasn’t from the same religion or caste as me. Despite the odds, I took the risk and eventually married her.

After we got married, we took another risk together—deciding not to send our children to a conventional school. All this was happening while I had a very stable job at Hindustan Times, heading the internet division. Despite this, I left my job and started a software company, a content management company.

When that was going well, I left it all behind, sold everything without a penny, and started an NGO—again, with no money in my pocket. That worked out too. Now, DEF is 23 years old. It wasn’t just a one-time success. It kept going.

At DEF, we did everything we believed in, even without any initial funding. We experimented with new ideas and undertook projects that we felt were important. If you look at DEF today, it might seem like we’ve done a bit of everything. For us, it’s a playground—a place where we can try anything, and money follows. It works because we follow our hearts and our inner calling.

One key lesson I’ve learned is that we often don’t listen to our inner call or subconscious. But it’s as loud as your conscious mind. People often say, “Listen to your gut” or “Listen to your heart.” It’s the loudest voice inside you, and if you sit quietly, you can hear it clearly.

We often don’t listen to our inner call or subconscious. It’s the loudest voice inside you, and if you sit quietly, you can hear it clearly.

Today’s generation struggles with this. Even if they’re successful, they can’t find peace because they don’t listen to themselves. They’re lost, trying to follow everyone else. Following your path and listening to your inner voice is the key to finding peace.

Whether you call it rebellion or just following your true path, it’s the same. By following your inner calling, you make it easier for yourself. You become at peace with your chosen path, even if the rest of the world sees it as rebellion. But ultimately, you’re making it easier for yourself by being true to what you believe.

Simit: Do you think there’s a downside to this? You know, like, once you’ve completed something, you’re always thinking, “What’s next?” You constantly want to move on to the next thing. At what point do you reach a point where you say, “This is it”? Is there a downside to never being satisfied or truly happy? Because there’s always that risk, right? No matter what you achieve, you still feel like you want to do something else.

Osama: That’s a very good question. If you connect rebellion, following your inner path, and purpose, you won’t feel the constant need for validation. You won’t be doing things just for the sake of personal satisfaction; there will be a deeper purpose. Let me give you an example.

If you connect rebellion, following your inner path, and purpose, you won’t feel the constant need for validation.

We do digital empowerment, right? So, what is digital empowerment? We go to the poorest communities, find an enthusiastic girl there, and provide her with digital equipment. She becomes a changemaker at a local level, connecting people, providing services, and sharing information.

But while we’re doing this, we realise, “Oh, this village has great music!” Music is also a form of wisdom and expression. Why not digitise that and let the world know about it? And then we discover, “Wait, this girl is also an artist!” So, we capture her art and share it with the world as something unique.

While we’re at it, we think, “This girl is making sorghum (jowar) roti, which is healthier than bread. Why not use the digital platform to promote sorghum roti and educate people about its benefits?” As we delve into this, we find ourselves exploring organic farming, natural agriculture, and more. Everything starts to connect: digital platforms for sharing knowledge, helping the poorest sell their crafts, and creating markets for their goods.

From an outsider’s perspective, it may seem like this person, who was once selling computers, is now an artist, a musician, and even using a natural toothbrush (datun). They’ve moved from making bread to making healthier food choices and are now meditating and practising yoga. It all happens in one day, but everything is linked, you see?

Similarly, we discuss detoxing, upcycling, and being mindful of how we dispose of things. We’ve digitised so much, yet we need to be more mindful of our carbon footprint. Can we upcycle? Can we use the same computer to make something new? This led to the concept of the circular economy, which is now a growing market.

All these ideas fit into different sectors and baskets, but they are all interconnected. They’re all derivatives of each other. So, it’s a full circle where everything comes together. And when you digitise, you need to think about the entire lifecycle—from the moment you buy a computer, to where it goes when it’s no longer in use, to how it can be recycled.

This same philosophy applies to eating. Before you even eat, you consider how it will affect you. You think about what’s going into your body and how it will make you feel the next day. It’s all part of the same cycle. We are mindful about how much spice we consume, just like we should be mindful of the impact of the things we use.

It’s all cyclical. Everything we do has a cycle, whether it’s in our personal lives or in the work we do every day. And that’s how it all links together. You can choose not to do something, and that’s okay. But let’s keep on living, keep doing what we can, and accept that some things are beyond our control.

Take AR Rahman, for example. If he makes great music, we could digitise it, but if we feel excited about it, we should go ahead and do it. The key is not to pressure yourself. You’ve written the advocacy, now let someone else take action. Focus on what you can do and be at peace with what you can’t. It’s okay not to achieve everything.

Focus on what you can do and be at peace with what you can’t. It’s okay not to achieve everything.

At the end of the day, this organisation is meant to do social work. We are just the carriers, the middlemen passing on resources from here to there. As long as we’re creating social impact, it’s fine if we don’t reach every milestone. Peace of mind and contentment with what we’ve achieved are what truly matter.

Simit: Yes, but in a broader context, do you ever feel like your mind is constantly at work? You’re always thinking about several things at once—this and that—and you’re juggling so many tasks. Do you ever feel overwhelmed? For instance, when you’re on a family trip, are you still thinking about work? Do you struggle with switching off and then switching your mind back on when you need to?

Osama: Yes, it happens quite often, and sometimes it just switches off automatically. For example, I could tell someone from my team, “I met Simit, and he’s digitalising Bhojpuri folk songs. Let’s collaborate.” I tell Akanksha about it, and she thought, “Oh, Sir has a new idea, and I need to work on this.” However, Akanksha already has a lot on her plate, so she often forgets to check her email or follow up on certain things. I forget too, because there’s only so much one person can handle.

However, if someone provides resources for the project, the situation becomes different. It’s no longer just something I’m doing on my own. There’s a clear difference between self-initiated work and a paid project. If I’ve raised funds for a project or partnered with someone who provides financial support, then it becomes a matter of professionalism. I have to deliver the project because now it’s about accountability. You don’t have to rely on yourself entirely—then you have a team to rely on.

The real challenge is that we have a policy in our organisation: once we start something, we don’t let it close down. For example, if someone has started a centre and it has been running for a year with financial support, we ensure that the centre continues to operate. It won’t close down. The strategy is more important than anything else. Our strategy is to ensure that every investment, from any partner or donor, is converted into a sustainable enterprise wherever we work.

We don’t view social work as charity. For us, social work is a natural way of functioning. Profiteering is unnatural—it’s the commercial, profit-making model we see in businesses. When we undertake any work, we aim to ensure that the resources are utilised in a manner that creates a lasting impact, extending beyond our own existence.

The real challenge is that we have a policy in our organisation: once we start something, we don’t let it close down.

That’s a core principle we try to embed in all our efforts.

Simit: The question I was asking, and what you answered, is more in an organisational sense. But what I’m really wondering is about the personal aspect for you. How much can one person handle? You might be good at doing many things, but there’s always a limit to how much one individual can take on. What are your thoughts on that? How does it affect you personally? There’s a quote that says, “If someone else can do the work you do at 70% efficiency, that’s still okay.”

Osama: Yes, thank you for reminding me. For the last ten years, thankfully, I can say, I’ve come to realise that I can’t be everywhere, I can’t do everything, and I can’t enjoy everything. I can’t write as many columns as I used to, and even when I have issues, I just don’t have the time for it. Over time, I began to feel the same level of satisfaction when any of my team members accomplished the same tasks.

For example, if we were to digitalise work with you and record Bhojpuri songs, I might have thought, “It would be nice to go for the recordings, visit the localities, try local food, and do all of that.” But now, I feel just as satisfied knowing that someone from our team has done it. I feel equally happy whether I do it myself or someone else in the organisation does it. We need to consider the broader perspective.

If you look at the map, we have over 2,000 centres. I haven’t even visited 500 of them, but I still feel equally happy and connected. Last year, we hosted a massive event that drew 1,200 people together in one place. I realised that they felt just as connected, even though I wasn’t physically there. They appreciated that I couldn’t be everywhere, just as I appreciate that I can’t speak at every conference. But when someone from my team goes, I ask them, “How was it? What were the responses? What were the questions?” And when they tell me, I feel like I was there myself, giving the speech.

You need to have enough love and passion for the work to understand that you don’t have to be everywhere. It’s like having a child: when your child does well, you feel good about it too. Similarly, I feel just as satisfied when someone else in my team performs. My eyes light up even brighter than theirs.

You need to have enough love and passion for the work to understand that you don’t have to be everywhere.

Thankfully, our organisation has the capacity to handle so many tasks. There are so many people capable of doing the work that I once wished I could do myself. It’s a great thing, really. It’s like having all five fingers of your hand performing on their own, and you’re enjoying that as well.

Simit: At what point do you realise that? When you start off, maybe with a team of 5 to 15 people, it’s manageable. But as the team grows and expands to 300 people, that realisation shifts. When did you recognise that, as your organisation grew, you needed to branch out, hand over responsibilities, and depend on others? And what if they’re not as efficient as you? Didn’t you worry about that, especially in the beginning? Did the thought, “If I had done this, I might have done a better job”, ever cross your mind?

Osama: No, no, I don’t experience this at all. Yes, I do think that certain things haven’t been done properly, but I don’t think in terms of, “I could have done a better job.” Thankfully, from the start, my leadership has never been associated with narcissistic personality. I’ve never had that kind of mentality of, “This is my job, and I should be the one to take credit.”

Number one, I’ve always believed that while the social organisation may have been started by me, it’s not my property. It’s not my company. Ultimately, it’s something that can’t be done alone; many people are needed for it to succeed.

Secondly, I have a DNA of detachment. I don’t get attached to fame. I’m sure you can see this from a distance. I’ve never felt the need to be the famous one, I’ve never been driven by the desire to be known for my work. I’ve always believed that my work should speak for itself. I don’t focus on legacy, or “my” this and “my” that. I never thought that way.

You can probably tell that I don’t indulge in “selfie mode.” This mindset has really helped me. It’s kept me from chasing fame, power, and recognition.

Lastly, I never regret something I couldn’t achieve. I don’t wallow over missed opportunities or things I couldn’t gain. I also don’t feel the need to indulge in or over-celebrate the things I have achieved.

So, there’s no excessive enjoyment, no overindulgence in my accomplishments. I think there are certain virtues that have been given to me, and I feel lucky that these things don’t bother me.

I have a DNA of detachment. I’ve always believed that my work should speak for itself.

Simit: While growing the organisation, did you ever feel the need to unlearn certain things? Were there any thought processes or perceptions that you felt needed to be changed as your organisation expanded?

Osama: Not really. I’ve only learned along the way. One thing about me is that I naturally trust people. In fact, I always say that I trust people until they prove themselves untrustworthy. And in that process, I never feel like I’ve lost anything—it’s them who have lost, not me.

Having said that, there’s something called compliance. When you’re running an organisation, and especially when you’re driven by passion and compassion, you can’t compromise on compliance. The rules of the land, the law of the land, paperwork—all those things are crucial. You can’t say, “I’ve been working honestly, yet this notice has arrived.” What I mean is that your work should be clean, and so should your paperwork. Not just your work, but your documentation should reflect the same integrity. It should show that you’re working cleanly, and everything about you should demonstrate that.

We’ve always made sure that we never compromise on compliance. That’s actually been one of the key factors in helping our institution become what it is today. While there’s a lot of informality, and we maintain a simple culture in our social enterprise, you’ll see that when it comes to formalities and compliance, we’ve never cut corners.

Our entire team believes that we learn from every scrutiny and audit. It’s not about proving that our accounting is perfect; it’s about being open to feedback. If someone thinks there’s something wrong, we welcome the input and work to fix it. We’ve never intentionally done anything wrong—it may just be that the paperwork didn’t look perfect.

Because of all this, we’re in a position where these practices have served us well.

Simit: When you look back, obviously in hindsight, are there two or three things that you feel you could have done differently—either personally or from an organisational perspective?

Osama: If I really want to compare our organisation to what people might consider the top five organisations, then I could say, “I could have done this differently.” But honestly, I don’t think so. Whenever we’ve needed to make a change, we’ve trained ourselves to adapt. For example, in the last two or three years, we’ve been learning a lot.

We’ve never had a fundraising department. We didn’t think we needed one. But over the past few years, we’ve learned from the ground up, from the ecosystem, that it’s crucial to have a dedicated department, even if you’re well-known and people naturally come to you. We realised it was something we needed, so we started one, and it’s worked positively.

That doesn’t mean we’ve become entirely project-oriented or solely focused on fundraising. It’s about balance. Similarly, we’ve learned that people won’t give funds if you’re too rigid about how you do things. If you insist, “This is how we work, and this is how we’ll do it,” you might miss out. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) funding, for example, might require a bit of compromise. We’ve figured out how to show that we’re doing exactly what others want while still doing everything we believe in.

We’ve learned that people won’t give funds if you’re too rigid about how you do things.

It’s like in Dangal, where Aamir Khan’s character observed the coach and understood what he was doing. The coach was applying traditional methods, but Aamir Khan wanted to bring his own approach for his girls. This didn’t mean that the coach’s methods were wrong, but Aamir Khan felt his own way was better suited to his girls. He still applied the core principles of the sport, but he used a different approach.

Simit: Since you brought up the subject of fundraising, I’m curious about your thoughts on communications. Many organisations are somewhat hesitant when it comes to communicating their work. They think, “Yes, we’re doing good work, but why is there a need to talk about it?”

At what point, if any, did you realise that communications had to become a focus? Was it always an important aspect for you, or did it become more significant over time, as you recognised the value in sharing what you were doing?

Osama: I would say our organisation’s biggest and most advantageous point is storytelling. We always say, “Walk the talk, and talk the walk.” Never just do one; first, walk, then talk. But don’t keep talking without walking. However, that doesn’t mean you should ignore the power of communication. This is where I have an advantage, thanks to my journalistic and media background, which came naturally to me. I’ve always loved storytelling. But at the same time, I have no idea how to tell a story that isn’t true. If I were asked to tell a fictitious story, I would fumble immediately.

I would say our organisation’s biggest and most advantageous point is storytelling. We always say, “Walk the talk, and talk the walk.”

So, the pressure was on us to ensure that we first do the work and then tell the story. Once we were able to improve someone’s life, we’d love to share that story. Being a journalist and writing in newspapers and columns has been incredibly helpful. There’s no doubt about that. We’ve had that advantage from the start.

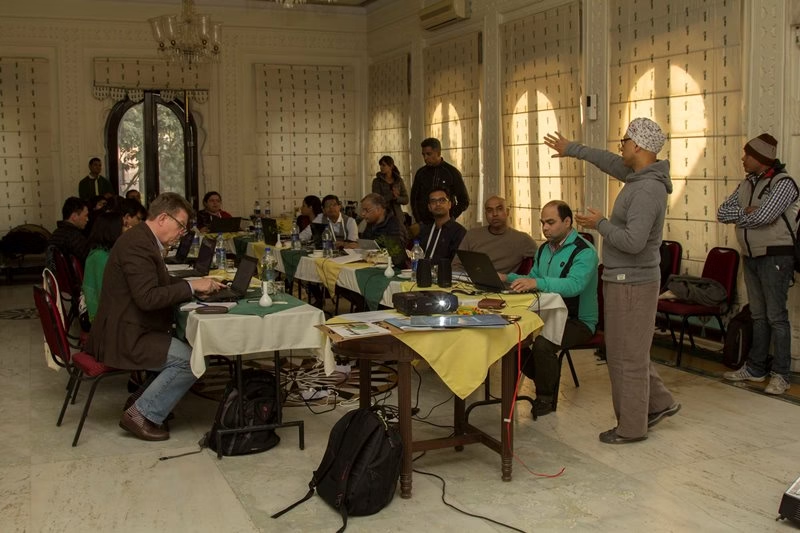

The second thing is that, you won’t find many organisations in the NGO sector with a communication department, research department, design team, graphics team, and film department all under one roof. We have all of those, and we don’t have separate funding for them. We have two filmmakers, four designers, five or six people in comms, and five or six researchers. This team is our largest, even bigger than our programme team. But the goal remains the same: these teams exist to support the programmes team, because all the work happens there.

Whether it’s films, brochures, or anything else, we do it all ourselves. The only time we reach out for help is when we have too many projects on our hands and not enough people to manage them. Our salary structure is also based on this approach. You won’t find many organisations that do this, especially social organisations, because they often don’t have the capacity for it.

For us, we even manage events with 1,500 people attending. We handle the sets, everything. We never outsource. And it’s not even my decision—if I tell my team to outsource, they wouldn’t do it either.

This approach, this mindset, has become essential for us. It’s not about just serving people, it’s about attaching ourselves to the details of what we do. We might sometimes spend more, or not know something well enough, but we figure it out because we believe it’s better to be fully involved in every aspect of our work.

It’s not about just serving people, it’s about attaching ourselves to the details of what we do.

Our structure is unique—whenever a project comes up, our researchers, comms team, and implementers all collaborate. Everyone contributes, and we work together to get things done.

Simit: Ownership is easy to spot when you’re a small team—say, 5 to 15 people. You can clearly see who’s putting in the work, who’s aligned with the mission, and who’s taking initiative. But as you grow—as the team expands to 300 or more—it gets harder. How do you build a culture where everyone stays motivated and continues to take ownership of their work, even at that scale?

Osama: I don’t know if I should answer this or if you should ask my team—how do they stay motivated and connected to the organisation’s goals?

But what I’ve seen is this: passion is contagious. If you’re passionate, that energy spreads to your team. If you’re honest and truthful in how you work, that sets the tone. It creates a culture where people hold themselves accountable—not because they’re being watched, but because it feels natural.

Passion is contagious. If you’re passionate, that energy spreads to your team. If you’re honest and truthful in how you work, that sets the tone.

When you build that kind of environment, people know they can’t hide. If someone isn’t doing the work or isn’t being honest, it shows. You might not catch it in a day or a week, but eventually, the missed deadlines, the undelivered tasks—they surface. And when that happens, it’s not your loss as a leader. It’s theirs.

So the real question isn’t how do you manage 300 people—it’s what kind of people are you bringing in? What kind of culture are you building around them? If the space gives them autonomy and trust, and if they feel personally connected to the work, they’ll perform out of self-respect and ownership. You won’t need to chase them down. That’s the kind of accountability we’ve built.

Simit: You know, as a journalist, I’ve always believed that storytelling should be authentic. That’s what the audience connects with. And I think that applies to organisations too—how they tell their stories, how they present themselves.

There’s also this idea of the personal brand and the organisational brand being closely linked. Like in your case, Osama, you’re a well-known figure. So how do you navigate that? How do you balance your own visibility with the identity of DEF? Does your personal image end up overshadowing the organisation, or do they support each other? How do you see that relationship?

Osama: This question often comes up in the social sector. But interestingly, in the corporate world, no one bats an eye when an 80-year-old founder is still actively leading the organisation. That same standard isn’t applied to NGOs—people are constantly asking when the founder will step aside.

In our case at DEF, we’ve been very intentional about this. From early on, we asked ourselves: how do we bring in younger people, how do we mentor and empower them? We also became self-aware about the visibility question—whether it’s me people are seeing, or DEF.

Initially, yes, I was the more visible one. As a passionate entrepreneur, I naturally had a stronger presence than the organisation. But as our work grew—work that clearly needed more than one person—the organisation began to grow and take shape in its own right.

Now, I’d say DEF has either reached parity with my name or even surpassed it. Especially in the past year, we’ve been very deliberate about shifting visibility to the institution. The idea is to use the founder wisely—for leadership, for guidance, for strategic appearances—but not as the face of everything.

And it’s working. People who earlier insisted on my presence at every meeting no longer do. Even government officials at senior levels are happy to engage directly with our team members. In fact, some are surprised when I do show up—they don’t expect me to be in every meeting anymore.

That, to me, signals a maturing institution. We’ve reached a stage where DEF is seen as strong and impactful on its own. Now it’s just about sustaining that shift—making sure the organisation continues to thrive beyond any one person.

Simit: Yeah. I mean, as the organisation was growing, were there moments where you felt, “Okay, this is the scale we’ve reached,” or “This is something we still need to work on”?

Would you say there were two or three things you personally felt you had to learn—or areas where you had to upskill yourself—as a leader navigating that growth?

Osama: Yeah, there are a few areas where I’ve felt the need to grow—or where I’m still learning.

First, I’ve never really had the skill set of a business development manager. I still struggle with reaching out to people I don’t know. It’s something I’ve never been comfortable with. But I’ve found a workaround—someone else in the organisation now handles outreach using our name, and that’s been effective.

Second, something we haven’t fully achieved yet is financial independence. Right now, we rely on inbound interest and people’s appreciation of our work. But that model isn’t entirely sustainable, especially if we’re thinking long-term. So we’ve been working hard to build a financially secure and self-sustaining organisation.

Third, we’ve always asked ourselves: how can we scale our impact without being directly involved in every initiative? For example, we’ve been developing DEF Chapters—like those in Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh—that follow our model and work autonomously. The goal is to create a strong framework that allows for replication without losing effectiveness.

Finally, we’re now exploring how to take our model global. Over the years, we’ve built a proven approach to poverty alleviation through digital empowerment. We’ve run hundreds of successful models, and we believe they’re ready to be adapted internationally.

Digital access has become essential—but it also comes with risks. Just like food is vital yet can be contaminated, digital tools are powerful but vulnerable. We’re working to build models that not only deliver impact but also protect the dignity, security, and rights of the communities we serve.

Simit: I have one final question for you. You’ve been working in the rural development space for over two decades now. If someone were to start an organisation today—especially in rural areas—is there any advice you would give? Anything you’d say they should or shouldn’t do?

Osama: If you’re starting out in the social sector, begin by making sure you’re solving a real, concrete problem. Don’t go in with just a vague idea or startup mentality—what’s essential is identifying a clear issue and having a practical solution in place. This clarity will guide your work and ground your mission in reality, not just aspiration.

Don’t go in with just a vague idea or startup mentality—what’s essential is identifying a clear issue and having a practical solution in place.

Next, it’s crucial that you do the work yourself before expecting support. Get involved directly. Use your own hands. Spend time in the field. Understand the community. Unless you’ve experienced the problem and taken those first steps personally, you won’t fully grasp what needs to be done—and others won’t be convinced either. When people see that you’re putting in the effort on your own, that’s when they’ll begin to trust you and feel motivated to support your vision.

Lastly, never start by asking for money. If your first question is, “Where do I get funding?” or “Who do I hire?”, it shows you’re not ready yet. In the development space, passion comes first. The ones who make a lasting impact are those who start solving the problem with whatever they have—without waiting for someone else to make it happen. If you show that you’re committed and already doing the work, support will follow. People are far more willing to help when they see you’re not waiting for permission or resources—you’re already moving.

If your first question is, “Where do I get funding?” or “Who do I hire?”, it shows you’re not ready yet.

Simit: Yeah, I mean, I could keep talking to you—there’s so much you’ve created, so much you’ve seen. But if you had to look back and name one big lesson from your journey in the social sector, what would that be?

Osama: I would say that working in the social sector allowed me to live the life I truly wanted—fully, consciously, and with purpose. It gave me a sense of dignity, like living on a grand stage with my head held high and my heart always beating for something positive.

People often say, “I’ve earned enough; now I want to give back.” But I always ask, “Why did you take so much in the first place that now you feel the need to give back?” Social work shouldn’t be an afterthought.

What I find strange is how many people, after reaching 50 or 60, suddenly say, “Now I want to give back to society.” But I ask—why did you wait so long? If you had to “give back,” does that mean you spent all those years just taking? Were you okay with the injustice and suffering around you until it personally inconvenienced you?

That mindset never sat right with me. I’m grateful that my wife and I found this path early on—when I was 34 or 35. We didn’t come into social work as a second act or a late awakening. We chose it when we still had the energy and the belief that things could change. Not to prove a point, not out of anger or frustration, but because it felt soulful. It gave peace, it gave satisfaction. It felt like the right way to live—not something we turned to after we had lived.

We didn’t come into social work as a second act or a late awakening. We chose it when we still had the energy and the belief that things could change. Not to prove a point, not out of anger or frustration, but because it felt soulful.

We always tried to listen to the voice of wisdom—and to common sense, didn’t act out of anger, and didn’t act to prove something to anyone.

We chose this path because it was soulful and it brought peace. It brought a deep sense of satisfaction.

It wasn’t a reaction but a calling and it felt meditative.

Simit: Another thing that often comes up is the conversation around failure. There’s always this debate in the social sector—should we talk more openly about our failures?

But I feel like it’s easier to talk about failure when you’ve already seen some success. What do you think about that?

Osama: I don’t really see failure the way most people do. What many call failure, I see as a phase of learning. There’s a clear difference between the learning phase and the phase of consolidation. Learning is when you prepare yourself—when you gather strength, skills, and insight for what lies ahead. You channel all that learning into something meaningful. In our case, that meant building an organisation that could bring people together and serve communities.

What many call failure, I see as a phase of learning.

For me, that phase of learning lasted from when I was 14 to 27. Some might call it a long struggle. But I think of it as a time of resilience, not defeat. I’ve lived through moments when I couldn’t find a job, had to borrow money just to survive, or walk long distances because I didn’t have ₹2 for a DTC bus ticket. I know what it means to carry rejection, disappointment, and uncertainty day after day. But I don’t consider those years a waste. These were life lessons—not failures.

And maybe because that phase lasted so long, the results we’ve been able to create now have been so strong in such a short time.

There’s this story I often remember. Someone once asked Rahul Dravid the secret behind his success as a batsman. And he simply said, “Anyone who has practiced 10,000 hours of batting can do what I did.” That struck a chord with me. His greatness wasn’t magic—it was about practice, patience, and persistence.

In life, we all face tough times. But the difference comes when you choose to apply what life has taught you instead of discarding it. Some people try to replace their life learnings with something they picked up from an MBA or a training course. But that knowledge is not always rooted in reality. The real transformation happens when you use the hard-earned lessons of your own life to grow and to build something better—not just for yourself, but for others.

That, to me, is the shift—from learning, to applying, to transforming your own life.

Simit: Thank you so much, Osama Manzar, for taking the time to share so openly—from the early days of struggle to everything you’ve built. There’s so much depth in the way you’ve reflected on leadership, learning, and living with purpose. I’m carrying back not just insights, but a sense of clarity about what it means to lead with heart. Truly grateful for this conversation.

Want to learn more about who’s shaping the social sector?

Subscribe to our newsletter for insights, inspiration, and real stories from the nonprofit and social impact world. From strategy insights to storytelling tools, real-world examples to conversations with changemakers, we explore what’s working—and why.